Many will say the military is perfect for people with little to no direction in life.

I’ll buy it for some, but for most, time in uniform allows Americans like myself the opportunity to be members of incredible teams, highlight individual strengths, and learn to lead from the front in the most conducive leadership laboratory that the nation has to offer. There is no better place to start out than in service to this Nation, which breeds inevitable growth for life’s adventures and opportunities to follow.

I could never have predicted I was bound for anywhere but a college within driving distance of home, followed by a desk job within the same radius. Thankfully, as a freshman in high school, I quickly noticed a standout group of seniors who chose to raise their right hand to serve following high school graduation. I recognized a common trend among these few, who were all bound for places like Quantico, West Point, Annapolis, Fort Benning, and Colorado Springs. Be it the enlisted or officer routes, these individuals were rock stars on the football field and baseball diamond, in the classroom, and in the community. They seemed to have an interest and ability to perform in a variety of disciplines, and what I noticed the most, was their care and concern for those around them. They had it all, or at least what I aspired to be one day: resilient, driven, and caring. I wanted to join the brotherhood that they had chosen to enter.

Flash forward four years later and I was the one in the barber’s chair, receiving my first haircut as a West Point “New” Cadet. In pursuit of a sense of community combined with my desire to be pushed to grow every day, I found the school’s parachute team. Over the course of the next three and half years, I traded every ounce of free time outside of studying and physical fitness to train to represent the school and the Army, while skydiving before sports fans and different communities in and around the northeast. The team made demonstration skydives into Yankee Stadium, Fenway Park, MetLife Stadium, Saratoga and Belmont Racetracks, and a whole lot more. Grit, attention to detail, teamwork, and a relentless pursuit of ensuring that the name on the uniform was cast in a positive light were only a few of the lessons being inculcated as a member of the Black Knights. To most that witnessed these jumps, they simply saw black dots falling from the sky, magic backpacks unveiling rectangular canopies, and smiles as black leather jump boots landed as close to the 50-yard line as possible. It was the overall effect, however, that I noticed was more than just two feet hitting the turf. They saw an act and a representation of the military that helped them connect with what was taking place overseas, and a window into a world of American military service.

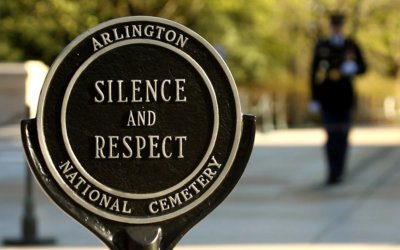

After school, I was commissioned into the Infantry and went through Army Airborne and Ranger school, two seemingly outdated programs that don’t necessarily apply themselves to modern-day combat operations, but instead serve as symbols of the Army tradition: to train and place one’s own safety second to preserving the safety of others. Later that year, I arrived at my first unit, the Marne Division at Fort Stewart, GA. As a Rifle Platoon Leader and then a Recon and Sniper Platoon Leader, we trained for a year and a half on small unit tactics, mechanized formation movement, urban operations, and dismounted reconnaissance patrols in preparation for a deployment to Syria. As the 14-month train-up winded down and we drew closer to the deployment date, the 2019 drawdown took effect, and our opportunity to employ what we had trained to do evaporated. I was crushed, and I wanted to channel my energy and training into something. Later, I remembered that I had seen that “something” 23 years earlier as a 3-year-old when I first witnessed the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery.

After a rapid change of direction and a thorough application process, I was fortunate to receive orders to Fort Myer, Va., to take command over this collection of selfless servants, known as Tomb Guards or Sentinels, who conduct a 24-hour, 365-day a year mission of preserving the sacred space that is the eternal resting place of three unknown service members, who represent the many who have given their lives in the defense of this Nation.

The changing of the guard, along with the few other major ceremonies and sequences that take place at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier appear straightforward and relatively simple. A senior leader enters through an opening in a chained-off area, to oversee the replacement of one guard for another, who has diligently and ceremonially kept watch over both the physical headstones as well as the aura surrounding them. The care and attention to detail, however, are the true reasons for the growing admiration for this sacred site. This enables our tight-knit team to communicate the history and significance of the grand symbolism of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to more than 10 million visitors annually.

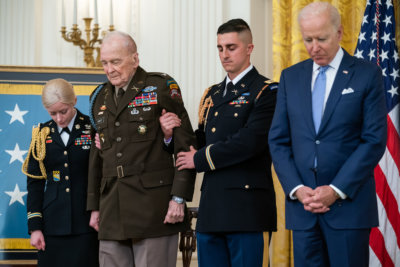

\During one of these historical briefings, I felt that everything I had done up until that point: the training, the long hot days, enduring old school West Point traditions, sleepless nights at ranger school; these aspects of my training enabled me to make a difference. And in doing so, I had grown in ways I didn’t think was possible. The same principles that I learned about on the parachute team came into play every day: grit, attention to detail, teamwork, and a relentless pursuit of bettering the larger organization every day. While not serving in harm’s way, taking care of those who have paved the way for us to serve today is a way we demonstrate our utmost respect. While we honor those who have given their life, much like the Unknown Soldiers, with the playing of Taps, the rendering of the hand salute and so much more, we have the opportunity every day to take care of those warriors who still walk among us, specifically those who have endured the horrors of war and done our nation’s bidding. I feel fortunate to be able to interact with many of these living heroes, who enter the gates of Arlington National Cemetery and walk up the hill to pay their respects to the Unknowns. Many of whom suffer from Traumatic Brain Injuries and numerous other combat-related injuries. My work as the Commander of the Guard is not only to take care of those laid to rest here but to provide a conducive environment for those suffering from wounds sustained in combat, both visible and invisible. It is my desire every morning that I come to work to ensure that these heroes can stand on the marble steps of the Memorial Amphitheater and be reminded and proud of the service that they have given this country.

I am thrilled to participate in the 22 Jumps and am in awe of the work that Tristan Wimmer has done to honor the life of the many, including his brother, who has served honorably. The endeavor to execute 22 BASE jumps successfully and safely, along with climbing out of the canyon under the Perrine Bridge, is no small feat. These events honor the immense sacrifices of those who have paved the way for us, particularly those living with traumatic brain injuries and those who struggle with mental health as a result of their wounds. People are this nation’s greatest asset, and these warriors deserve our support. Parachuting with Purpose brings well-deserved recognition and awareness to caring for these veterans, and I for one feel lucky to be able to contribute to this team effort to bring honor to these American Heroes.